Like a Flash of Lightning from a Blue Sky

by Martin Bartels

14 June 2022

Week 21 of the year 2022 Incident #1:

Imagine being at the supermarket checkout, having scanned all your goods and packed them into bags, only to discover, to your shock and embarrassment, that none of your plastic cards are working. The people in the line behind you start to grumble and cast critical glances in your direction as you sweat and fumble with your wallet searching desperately for another way to pay.

Such a problem occurred in Germany this year on the 24th of May. However, it was not simply an embarrassment for one unlucky shopper, but for an entire range of retail chains and petrol stations whose POS system software had failed.

The affected POS systems, which had been developed by an American company, had been introduced around 10 years ago, and have generally been considered very reliable, gaining a market share of around 40% of all POS systems.

Eliminating the problem, a process which is underway, will require not only updating the software but manual intervention to the hardware too. It is likely to take weeks.

Incident #2:

The same week that POS systems were causing retailers headaches in Germany, malfunctioning computer systems were creating chaos at UK airports as an airline abruptly cancelled around 200 flights. Over 30,000 passengers around the UK were suddenly told they would not be flying. It’s not exactly clear what caused the situation, but an "IT glitch" was named as the cause.

While it may be easy to blame the supermarkets and airlines for these messy situations, it is more useful to look more deeply at the structural causes.

The downside of netted technologies

When an embedded network repeatedly proves itself to be both quick and correct, human confidence in it becomes unshakeable.

However, the more a sophisticated technology has scaled up, the more it is equally capable of magnifying small and large faults and damages.

The probability of failures in professionally maintained systems should decrease with mass use. With repeated and widespread use, errors can be systematically located and eliminated. Yet, when faults do occur it can be difficult to predict the extent of the damage they can cause.

So while the probability of a total failure may be low, the potential scope of any damage makes the risk significant.

Where do the risks come from?

In the two above cases from week 21, the risk is to be assigned to the internal sphere of the respective institutions that operate with the system. Although these companies obtain the most important components of their technology from external developers and producers, they themselves are responsible for the process of selection, combination and calibration.

When programming software, the goal is always error-free code. Before it is used, each code is subjected to rigorous testing to be sure that every function works perfectly. If malfunctions occur in use, the developer takes feedback from customers as an opportunity to further perfect the code. The probability of errors thus goes steeply downwards.

In later phases, the effort to improve continues via software updates, which may be many years after the initial launch. These are also subjected to rigorous testing before deployment. If there are failures after these stages, as in the examples above, this is probably due to a software update or a lack of compatibility with hardware components.

Such failures are in contrast with external causes. These can be both with and without intention. Those without intention stem from unexpected expects such as natural disasters. One example is the very strong volcanic eruption, followed by a tsunami, of 15 January 2022, which, among other things, severed the only undersea cable connected to Tonga. This led to the country being cut off from communication with the rest of the world.

A more frequent disturbance is intentional, triggered by greed or hostility. Hackers may steal confidential information or freeze vital systems until a ransom is paid. With military means, it is possible to destroy communication routes.

"Inside jobs" cannot be ruled out either. This is the case when programmers, for whatever reason, build difficult-to-detect malfunctions into software in order to commit sabotage.

Users who suffer the consequences of systemic failure may be indifferent to the causes, as they are inconvenienced either way.

Thicker walls

In ancient times, when attacking armies had more powerful siege engines at their disposal, the castle lords would subsequently built more powerful ramparts and sometimes hidden escape tunnels. When we look at the remains of such structures today, it becomes clear that ultimately almost all fortresses were vulnerable at some crucial point to either force or cunning. They were not useless, though, because they provided effective protection over long periods, and possibly allowed people to flee in time through tunnels, thus saving human lives.

The situation is comparable today, as companies can be vigilant for potential threats and proactively keep upgrading their precautions to protect systems and their users. The law of supply and demand mitigates the problem but does not eliminate it. If users of a system realise that it is inadequately protected, the system's market share will decline, but unpleasant surprises cannot be ruled out even with the strictest quality requirements for a system. Inadequately protected systems are the first ones to fall to their knees, but not the only ones.

How to respond

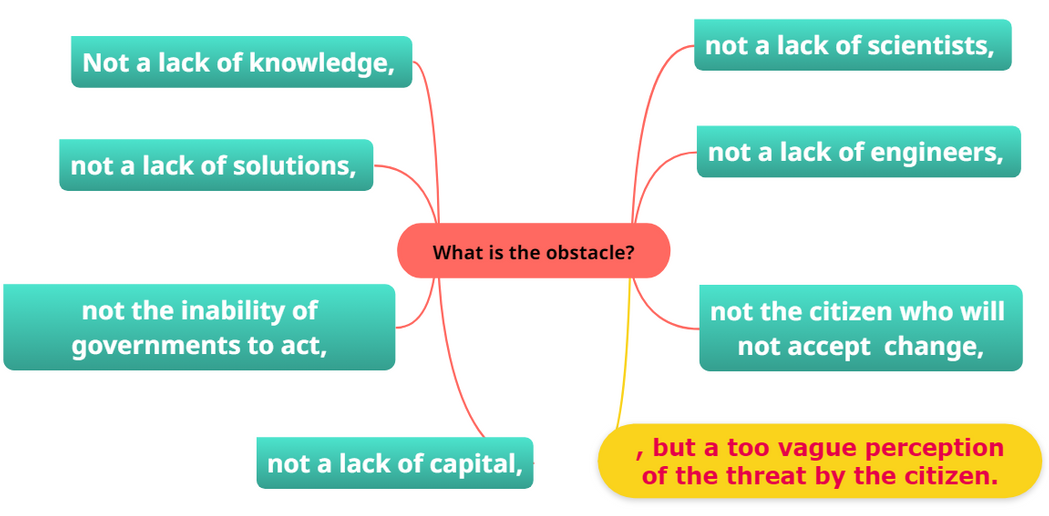

There are good reasons to be enthusiastic about powerful new infinitely scalable technologies. But there are no reasons for naïveté with regard to the damage that will almost inevitably happen to all systems given enough time. A system does not care about the magnitude of a negative external effect, and this is where systems diverge from human ways of thinking.

If a software system error has caused massive damage, this does not mean we must do without it or its replacement. The advantages of software for increasing prosperity and security are obvious. We also know that calls for more perfection cannot exclude risk, e.g. in public transport, logistics, electricity and water supply.

When a system no longer works, people fall back on previous solutions. They fetch their bicycle from the cellar or go on foot when the train doesn't run. They use cash when the plastic card no longer allows a purchase, and they light candles when the electricity grid fails. Citizens can protect themselves more easily by keeping a larger amount of cash on hand or by saving important documents in paper form. On the other hand, it is gratifying that in times of systemic collapse, experience shows that there is an increasing willingness for mutual aid and helping those who are particularly exposed because of their age or infirmity.

While calls, especially from young people, to abolish physical systems (cash, metal keys) altogether are nonsense, we may still need the old-fashioned techniques in case of emergencies, even if they are slower. Some people also like them better, and that should be respected.

Functional fallback positions and strategies to diversify risks are necessary. And we should only give in to the enthusiasm for electronic solutions for simple tasks such as opening a locked door if we additionally install a mechanical solution for the case of a system failure.

Companies that are responsible for the infrastructure and operation of data systems are aware and monitor for systemic failure risks. They work with elaborate backup systems and use geographically separate locations for their server farms, for example. But even these will stumble if, as in the unfortunate example of Tonga, a data connection fails for a long time.

Conclusion

Enjoy the benefits of technologies that make life easier, but always be prepared for sudden outages. Laxness can mean pain. When systems fail, we need to be prepared to smoothly shift back to older solutions, even if it’s just for a short while.

Even before the POS disaster was over, a well-known retail bank announced that it is now preparing to stop holding cash in its branches in order to save costs. Has it miraculously managed to ensure the infallibility of its ATMs for all time?