Stupidity: Are We Looking in the Wrong Direction?

Martin Bartels

3 September 2022

How we understand stupidity

According to the common understanding, stupidity has something to do with the inability or unwillingness to think in an orderly manner.We do not feel a strong urge to define the term more precisely, because each of us experiences so much stupidity around us almost every day that no need for an accurate description arises. At work, in politics, and even in science and charitable organisations, possibly in our own wider families, stupidity seems to grin at us. Stupidity appears to be so overwhelmingly evident and arouses so much aversion that we find it difficult to deal with it soberly.

Change of perspective

The conventional understanding of stupidity as the absence of the ability to think properly cannot actually be correct. Simple experience disproves it: Anyone who has ever had a discussion with a dedicated conspiracy theorist, for example, will no longer doubt his or her capacity to think. Such people can erect and develop the most complicated thought structures in an almost acrobatic way. They search obsessively to find endless details that substantiate their conclusions. Clearly they have a capacity for thinking, even if the output is manifestly wrong.

In 1976, the Italian economic historian Carlo Cipolla published an article on the subject of stupidity titled "Le leggi fondamentali della stupidità umana", the English translation of which is titled “The Basic Laws of Human Stupidity”. Cipolla radically changed the view on stupidity, moving away from the woolly prevailing opinion towards an innovative and more precise understanding of the phenomenon. The essence of his approach is not to understand stupidity in terms of the ability to think, because that is only a potential that can be used in various ways. Rather, he identified the decisive criteria to be behavioural patterns firmly rooted in the personality. The practical value of his approach is that we can better assess the dimension and dangerousness of stupidity and even work on defence strategies.

Cipolla’s system

You may have seen a warning sign on a garden door in France that says “Chien bête et méchant” = "Stupid and malicious dog". This is an expression of subtle black humour, and yet the message has a chilling effect when we think of the dog's chaotic willingness to bite without reason. Such a dog would embody what Cipolla has identified as real stupidity.

Cipolla’s definition of a stupid person as one who is determined to indiscriminately harm other people as well as themselves does not exclude the ability to think accurately. Rather, the thinking capacity of a person of this type is the arson accelerant with which he or she can maximise damage. The blindly stupid person finds fulfilment in damage, regardless of short or long term implications.

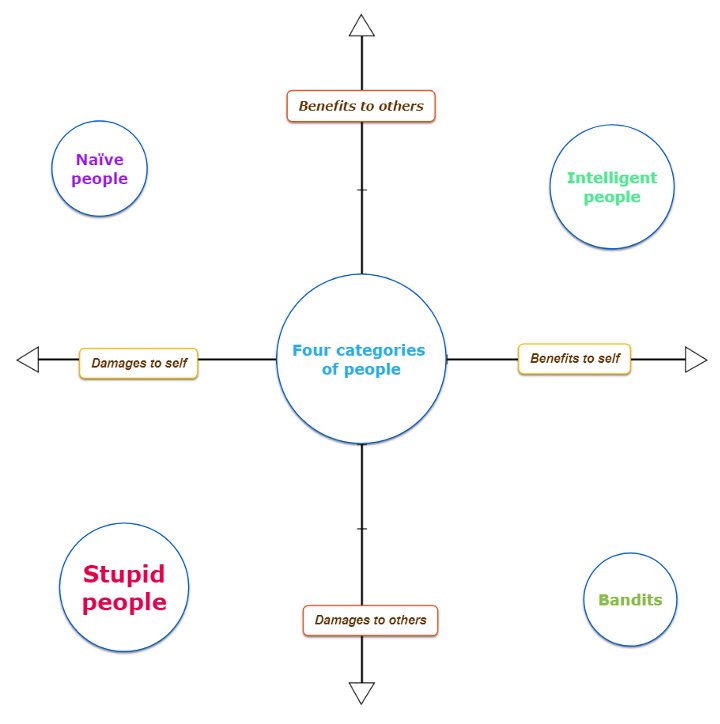

As the following diagram shows, Cipolla’s understanding of stupid people becomes obvious when considering their opposite, i.e. intelligent people. The latter, in fact, are naturally anxious to benefit others and/or themselves with their actions. They are committed to what economists designate as “Pareto improvements”. Intelligence understood in this way can be linked to the ability to think sharply, but this need not be the case. Rather, the decisive factor is the consistent intention to generate benefits and the ability to recognise the need for reasonable action. These qualities are anchored in personality.

Naïve people have similar propensities, but are to be distinguished from intelligent people. Naïve people believe in generating benefits, but still feel good about their actions even when they cause self-harm.

Then there is the bandit class, those who are convinced that they can only gain advantages for themselves at the expense of other people and who operate with deception and violence.

All except the stupid can find themselves in a different quadrant in different situations or states of mind. Thus, it is not impossible for a member of the bandit class to act in the mode of an intelligent or naïve person when an impulse to act arises that has nothing to do with enrichment.

Only the people in the lower left quadrant are averse to any mixture; they are steadfastly committed to causing damage.

What makes the stupid particularly dangerous

The stupid, according to Cipolla, invariably make up an integral part of any group of people. Those who do not belong to the stupid quadrant always underestimate the number and the strength of the stupid, and they do not understand their motives. In particular, they don’t grasp why and to what extent stupid people are uninhibitedly to harm even themselves with full awareness and vigour.

According to Cipolla, the probability that a certain person will be stupid is not correlated with any other characteristic of that person, i.e. education, thinking capacity, gender, social status, cultural background, religion and nationality do not make a difference.

The assumption that the stupid implicitly and invisibly follow a rational line of reasoning is for the non-stupid a seemingly logical projection of their own way of thinking. And it is a dangerous thinking bias.

The people from other camps who think they can ally themselves with stupid people will lose.

The most dangerous stupid people

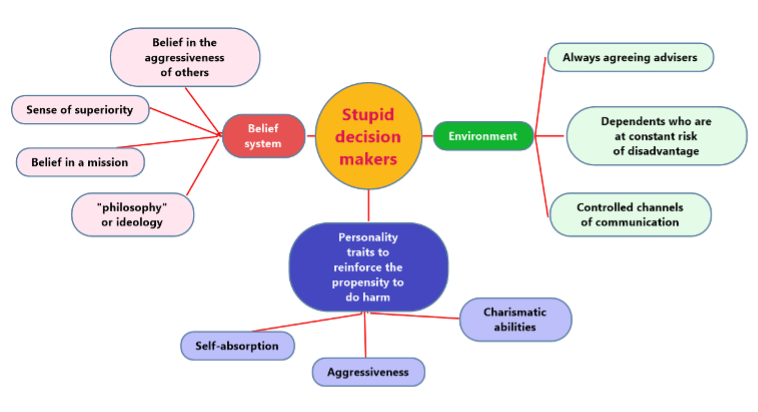

Stupid people are most dangerous when they have risen in their social framework, have abundant resources and wield power. Their personality traits, their belief system and a human environment that expects benefits are exacerbating factors. The following graphic is a tentative look into the abyss. It is a sub-case of the dangerous quadrant of Cipolla's model.

It is unlikely that the totality of aggravating (or mitigating) factors can be identified. After all, wild imagination gives wings to people from the stupid quadrant. Imagination can be trained like a muscle.

How can we deal with the critical quadrant?

Stupid people cannot be imprisoned or dumped of in any other way. Stupidity per se is not a crime. We can only continually strive to identify them and endeavour to contain their actions or at least the impact of their actions.

Since the decisions of people from the dangerous quadrant are something of a realm of darkness for the rest of humanity, there is an obvious antidote, namely transparency.

The development of modern industrial societies is gradually moving in the direction of shortened and more transparent hierarchies within social organisms and increasing disclosure to external stakeholders (e.g. shareholders, clients).

The protection of whistle blowers who expose abuses is recognised as serving the public good. Entities that act in a non-transparent manner and violate emerging social value systems gradually come under pressure from stakeholders and capital providers. A company that violates sustainability standards, for example, makes its own access to capital more difficult.

These are recent developments that can change direction or weaken. Nonetheless, given that ongoing interaction tends to reduce the error rate of social systems, the increasing spotlight may gradually amount to a reduction in the power of the "Cipolla stupid". This should improve the efficiency of social systems.

The previous paragraph is intentionally worded very cautiously. But it is generally true: light dispels darkness.

How robust is Cipolla's stupidity theory?

Cipolla has sharpened the eye for diagnosing pathological social phenomena. The existence of people, especially in higher positions, who blindly harm other people and themselves is something everyone can confirm from their own experience or by reading the press. Cipolla’s theory of stupidity highlights this and is more helpful than the popular and clearly too simple idea that stupidity is the same as a weak thinking ability. Nonetheless, the assertion that stupidity exists and works completely independently of the ability to think does not go down easily.

The ultimate test that a theory in social science must pass is still outstanding, namely the empirical verification of Cipolla’s assumptions based on his understanding of stupidity. Since no empirical studies are available that would corroborate the massive presence and influence of destructive stupid people according to Cipolla's definition in really any group of people, caution is advised.

As an economic historian, Carlo Cipolla was firmly committed to strictly rely on facts. However, while his theory on stupidity is intriguing, he will certainly have been aware that this is not yet proof of its validity. We do him no injustice in presuming that he would, if he were still alive, be pleased if behavioural economists used their modern methodology to test his approach. Possibly four quadrants are not enough to capture reality. In the outstanding discovery process, other facets are likely to emerge that will that translate into progress that is useful for modern society.