Covid-19 in 8 Verticals

COVID-19 in 8 Verticals

Martin Bartels

15 March 2020

Introduction

Following the logic of Donald Rumsfeld‘s 2009 lesson on the degrees of uncertainty

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GiPe1OiKQuk,

given in a completely different context, the pandemic haunting us now has become a “known unknown” through Larry Brilliant’s 2006 TED speech:

https://www.ted.com/talks/larry_brilliant_my_wish_help_me_stop_pandemics.

We should have acknowledged that it was coming. Since December 2019 it is a “known known”. Now we perceive it primarily as a risk factor that threatens our health and that of our loved ones.

Our best researchers worldwide are working on medical solutions. We can be confident that they will succeed and free humanity from this threat.

It is time to realise that the health crisis is nothing more than a tiny needle that causes a big beautiful balloon to burst. It is putting an end to a state of over-extension. The impact of the “COVID-19 needle” on the global economy is more serious and lasting than the health dimension of the change.

Such phenomena are not unusual: The reason for WW I was not the fact that Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s driver got lost in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 and accidentally turned into a street where there happened to be an Austro-sceptic with a pistol in his pocket. The real reason was a complex state of tension that nobody wanted to admit at that time.

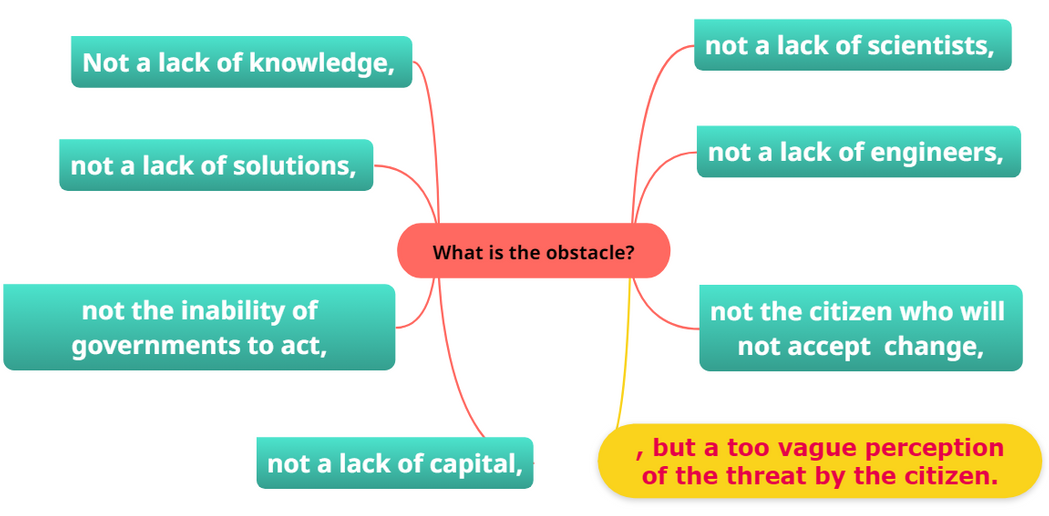

Through often tragic detours, we have learned in the meantime to deal with health crises more rationally than e.g. at the time of the “Spanish” flu. Presently we are mostly impressed by the way our governments accept the guidance of first-class scientists and adjust their crisis management accordingly. The scientists use clear language that every interested listener understands. People and governments accept their conclusions. This is both a necessary and pleasantly surprising qualitative leap forward.

The virologists exchange information globally with each other, and their scientific approach, which is committed to rationality, saves human lives. Of course we are worried, but we are better off by following the wisdom embedded in Mark Rylance’s “Would it help?” question.

So it is only reasonable to take the virologists as an example and search for the causes of tension with a medical mindset. Sentimentality and too much attachment to old thinking habits would jeopardise or prevent adequate treatment.

The perspective presented here is that over the past few decades value chains for many important industrial goods have developed into a state of over-extension. Cost advantages from the relocation of industrial production to distant locations became risk factors. The costs now caused by a pandemic indicate that these risks have materialised to a large extent already.

The necessary repair work needs to be carried out rationally. This means that scarcer resources must be used strategically with a longer term perspective. The aim is to restructure national economies in a cautious and circumspect manner. Each sector has its own logic. And of course there will always be regional differences.

It is now possible, with probabilities of well above 50%, to deduce which change is imminent in which sector. Some of the expected developments have already begun. There will be winners and losers. Both sides deserve support. Otherwise we would endanger the stability of our societies.

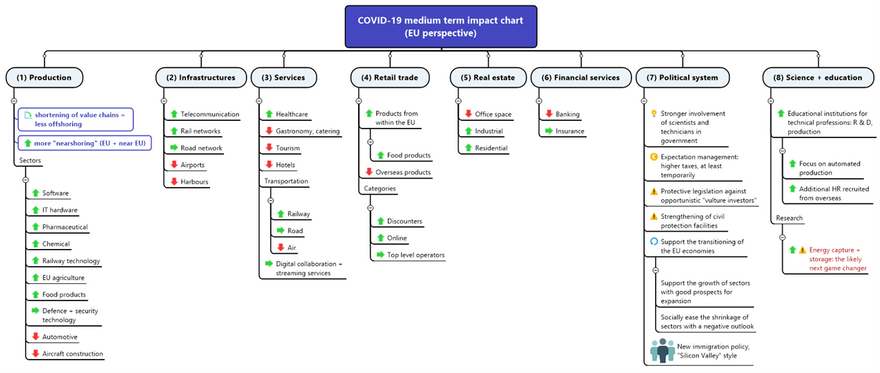

Our “COVID-19 Impact Chart” browses though the expected changes from an EU perspective. This chart is an attempt to describe medium term effects of the pandemic. It is widely self-explanatory. Some points may give rise to discussion, but a consensus on the direction of developments is quickly reached.

(1) Production

The EU is a region with few natural resources. So it is competitive production that is predominantly responsible for the region’s prosperity. There is growing consensus that value chains need to be shortened. The point is that the lower cost of human resources in distant locations can be compensated, gradually, by automated production in the Union or in its vicinity.

In the field of financial services, regulators have for some years been emphasising the importance of moving critical IT systems out of offshoring. They wish them to be developed and operated within the Union: "nearshoring". This way of thinking is now being transferred to the industrial sphere.

Cost advantages can still be achieved with nearshoring, but the decisive effect is the reduction of exposure to shortfall risks.

Nearshoring may also allow additional risk reductions by diversifying production sites within the Union or in neighbouring countries.

There are already painful bottlenecks in the pharmaceutical industry resulting from excessively long value chains. Probably the most critical vulnerability we have is in IT hardware.

The very important automotive industry is struggling with technological bottlenecks because consumers are still waiting for drive technologies that offer or surpass the performance of combustion engines. The pandemic is increasing consumer reluctance, which has built up over the years.

Aircraft technology will suffer from a new and powerful trend against flying, partly driven by ecological arguments. Public transport will benefit somewhat, but overall Europeans will travel less. The lifestyle adopted in quarantine with less movement over distances has found followers.

(2) Infrastructure

Large parts of Europe suffer from inadequate telecommunications infrastructures. The pandemic made this deficiency abundantly clear. Compensating for this competitive disadvantage will boost the growth of equipment suppliers.

The need to renovate the railway network and, to a lesser extent, the motorway and road networks, is significant.

Additionally, discontinued railway lines can be reactivated.

The construction of new railway lines may be hindered by legal obstacles and tendering procedures that lead to unsatisfactory results. Nevertheless, the renovation works will entail a significant boost in demand for the construction industry.

Ports and airports will feel a reduction in the use of transport routes.

(3) Services

Over the last 20 years, there has been a pressure to cut costs in the health sector almost everywhere in the Union.

At the same time, professional and tourist mobility has expanded to such an extent that existing infrastructures have often reached their limits and many people have increasingly found their own behaviour stressful. The crisis triggered a reversal of trends in both areas. The effects will diminish, but will also continue.

First-class electronic means of communication with video functionality have proven their value in the crisis. However, a significant economic impact in the telecommunications sector is unlikely, as these services are rapidly becoming low-cost or even free.

(4) Retail trade

The pandemic has done great damage to the retail sector and has given wings to online business.

The effects on European urban structures are painful and only partially reversible. The trends have existed for years and have now become established.

The demand for food from the region has increased.

Established discount chains have the best chances for growth, if they continue to improve the quality of their product range. Specialist shops will find it more difficult to cover their costs in view of online business.

(5) Real estate

Some companies have been experimenting for years with the relocation of electronic work to “home offices”. Since March 2020 this suddenly became a necessity. Despite widespread difficulties with inadequate hardware and unstable access to corporate servers, there is now a consensus: the imposed experiment is a success.

If employees no longer come to the office every day, less office space is needed. At the same time, the workplace at home becomes more valuable. This should result in a reduction in demand for office space and a strengthening of demand for residential property.

The demand for industrial real estate should also increase where new production facilities are to be built, to shorten global value chains.

(6) Financial services

The crisis of 2020 is not coming from the financial sector. But it is having an impact there by reinforcing existing trends.

The contraction of the economy will lead to credit defaults. Not all bank branches that were closed during the quarantine will resume their operations, some will be closed after a few months. Online services will fill the gaps.

At the same time, the Europeans' love of insurance policies will remain intact.

(7) Political system

There are no arrows in this vertical. They might give the reader the impression that we are talking about simple changes in volume. But reality is more complicated:

Still reeling from the impact of the last crisis in 2007/2008, public administrations are once again faced with major responsibilities. Governments must understand the structural changes that are taking place and reinforce trends in sectors where new opportunities are emerging. They must also mitigate change in sectors with a clearly negative outlook, without making vain attempts to stop it. Wrongly allocated tax money will be lacking in those areas where the foundations for new prosperity need to be laid. The strategically correct distribution of subsidies is a demanding task. At this stage we need the advice of first-class macro-economists and deafness to lobbyists.

The life-saving contribution made by scientists during the health crisis before the eyes of the public results in acceptance. Citizens are showing gratitude for the advice of experts to an extent never seen before. This has a lasting impact on gaining social consensus in general. In the future, citizens will expect more scientific support for economic decisions than in the past.

Public sector disaster protection is well developed, yet it must take into account that disasters, even if not correlated, can cumulate and be mutually reinforcin:

The capacities for this function must be further developed.

When governments are called upon to reorganise and revitalise economies as quickly as possible, this cannot be a free lunch. Comparable to the “solidarity surcharge” for the economic reconstruction of East Germany, special taxes will be necessary for a few years. The states of the Union need to communicate this to their citizens in an understandable way and with the help of first-class economists. A lack of clarity can provoke or intensify social unrest.

Europeans must also be prepared to accept that the road out of the crisis will be longer or not at all successful unless they embrace an immigration policy that contradicts their traditional attitude: The Union will not be able to provide the urgently needed economic recovery with its own human resources. Immigration laws must be adapted so that valuable expats, in particular highly qualified engineers from all over the world, can easily enter Europe and feel that a red carpet is being rolled out in front of them. With new guests, there is more food on the table for everyone involved, European traditionalists included. Half-heartedness is tantamount to decline. Fortunately, there are befriended countries from which we can learn a lot in this field. We should ask them for guidance.

This section has no box for the unconditional basic income project (“UBI”). The question undoubtedly concerns us, but in view of the tasks now facing us, it cannot be tackled in the medium term.

(8) Science + education

Europe has a historically developed excellent public and private infrastructure for training technical specialists and for research. There is every reason to expand and strengthen it, also by inviting more experts from overseas. The electronic video media, which have now become popular, can help to meet the growing demand with high-quality teaching or consultation with overseas partners.

And we should buckle up for the next major industrial impulse: the very significant investments made over decades in research in many areas of energy production and storage are gradually leading to the conclusion that the bottleneck factor "expensive energy" will soon be matter of the past. This change is still a "known unknown", but well on the way to becoming a “known known”. When it materialises, we will experience this improvement as a structural crisis before we reap the benefits.

For now, the opportunities and risks of COVID-19 continue to deserve our full attention. It is unlikely that the Union will initiate a change process which overseas partners will find very disruptive. Globalisation won’t end, but its structure will change for good, gradually.

Suggested further reading: